The Bestiary of Christ: The Crustacean, The Remora, and the Pike

Crustaceans:

Symbol of the Invulnerability of Christ

If the idea of representing Christ the Warrior in the image of a dolphin occurred to Christians in the Roman period, as has been evidenced by Adhemar of Angouleme’s pontifical ring, how could their thinking not have been turned, with the same intentions, to the armoured fish, to the crustaceans which nature graced with defensive and offensive arms? (Fig I).

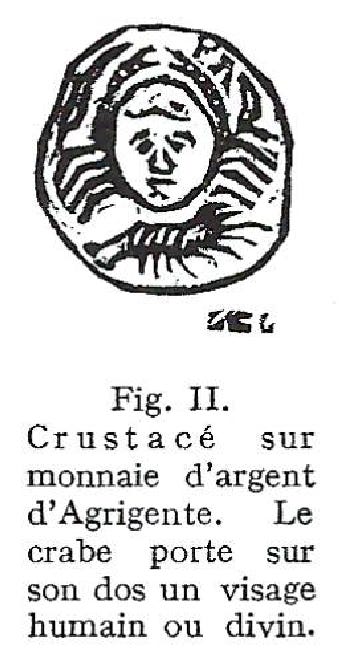

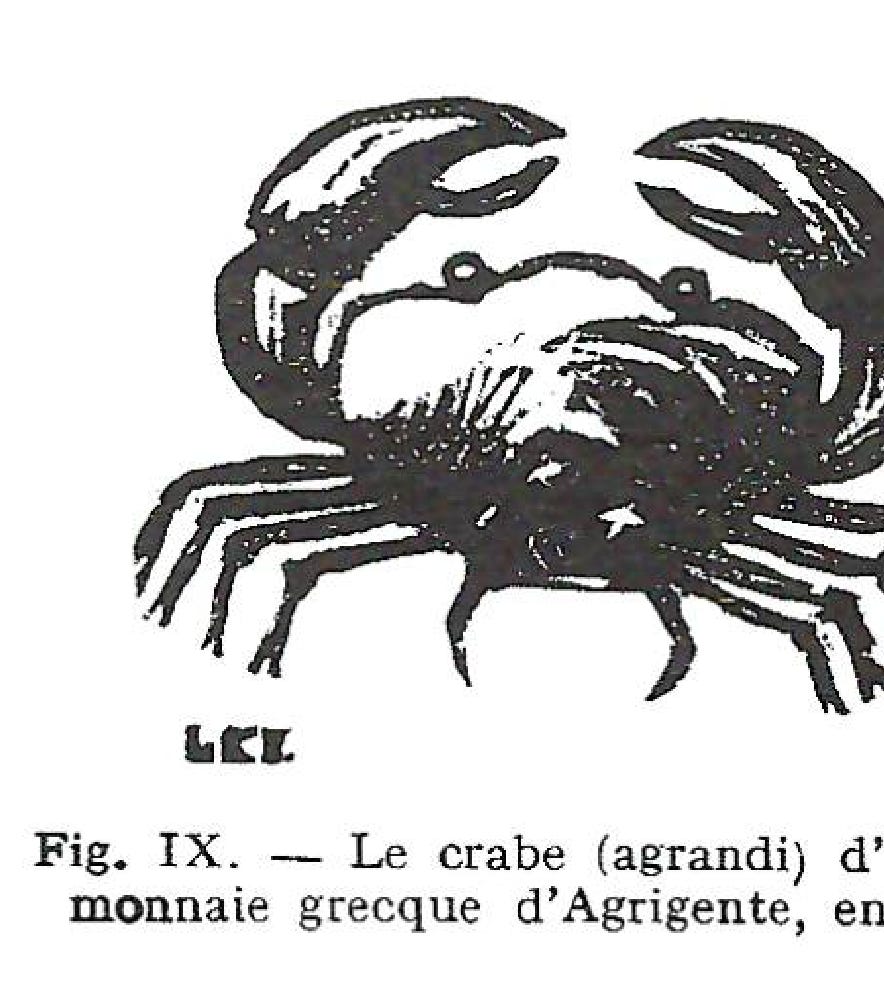

They were not wholly unknown or ignored in the art of the ancients, for we see them stamped on the most beautiful gold coins, those of Metya1, of Agrigento (Fig II2), of Himeria (Fig III) in Sicily3, sometimes, for example, with a human head.

Did these cuirassed animals not call to mind those famous heavily armoured warriors, the ancient cataphracts whom Lampridius4and Tacitus5 described so neatly?

Otherwise, what other, more perfect symbol is there for the invulnerability of Christ, the eternally Victorious who pursues evil down to the darkest depths, to the abysses of the human soul, even?

A precious stone from the Foggini collection reproduced by de Rossi6 and the Benedictines of Farnborough7 (Fig. IV) depicts a symbolic crustacean and warrior with the satanic octopus, whose tentacles flail impotently, in its mouth. Below him the words ΙΧΘΕ ΣΟΤΕΡ, Ictus soter, the «Saviour fish»! And under him, the faithful fish swims confidently, protected by his invulnerable and victorious Guardian.

The body of the crustacean, furnished with a hard, laminated shell reminiscent of the «lorica» armour of the Roman legionaries8, ends with a hanging tail, particular to this genre of animals.

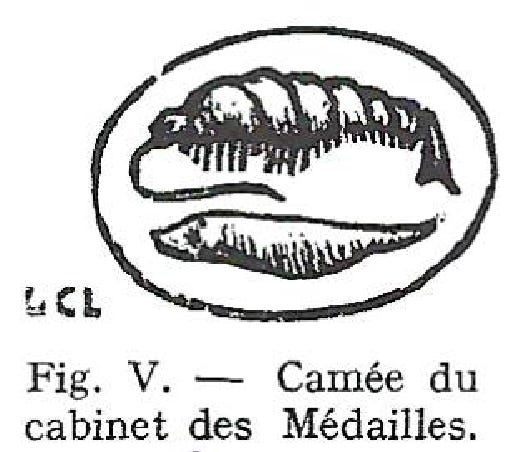

A cameo from the same time, number 145 from the Cabinet of Medals (Fig. V), also depicts a crustacean with a serpent-like fish in his mouth, more so a conger than an octopus. On this cameo, as on the Foggini gem, the faithful fish swims peacefully, close to his protector.

Finally, an amethyst which joined the Capello collection in 1702, reproduced by Gori9 (Fig. VI), shows a poorly engraved animal, who because of its lateral legs appears to be a schematic crustacean, since the inscription: ΙΧΘ, abbreviation of Ictus, shows that it is a fish and not an insect. This leads one to think the artist deliberately sought out to represent the mysterious and divine fish.

This Capello amethyst permits us, I believe, to consider plausible the depiction of crustaceans on at least one barbarian ring— from the fifth or sixth century— found in the province of Namur (Fig. VII) and published by Deloche10. Similar to the Capello amethyst, the schematic design is reduced to an oblong body preceded by a globular head and furnished with lateral legs. It should be noted that most subjects in Merovingian art, in France and elsewhere, were primarily religious in nature.

To end, I cite a bronze fibula from the same period. It portrays a crustacean from the family of the decapods, a crayfish or a lobster (Fig VIII). It seemingly should be placed chronologically between the precious Roman stones and the Namur ring, which it seems related to. We know that the fish motif, derived from the early Christian Ictus, was favoured by the Goths in fibula form. It is also thanks to barbarian art in the West that the Christ Fish, abandoned in Rome after the peace of Constantine in 314, regained its popularity in old Gaul during the following centuries.

Crustaceans were rarely depicted in the iconography of the Western Middle Ages, save as astronomical figures. Neither were they found on heraldry, save for a few exceptions in Germany, and these depictions were of a wholly secular order.

In the early Christendom of Western Asia, crustaceans, like shellfish, like turtles, figured as the emblem of Invulnerability.

The Remora

The Remora in Ancient Imagination

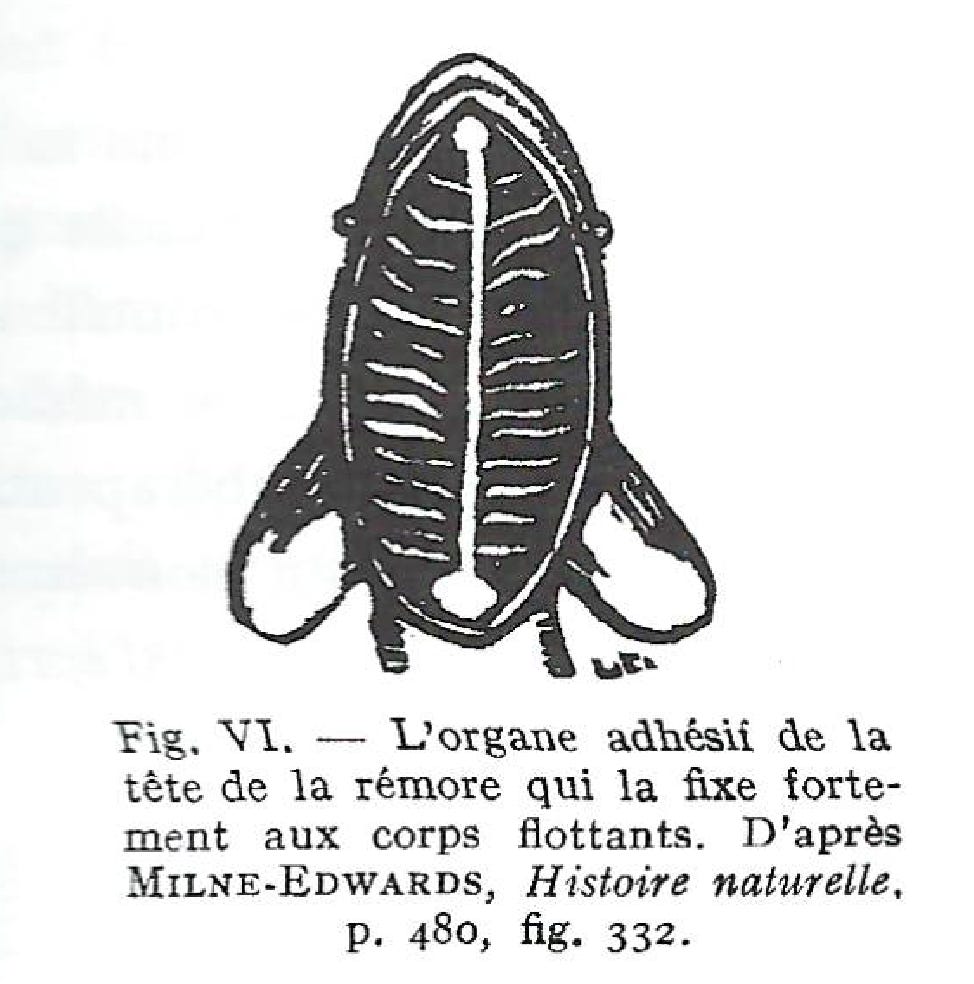

In the vocabulary of contemporary biology we call this little, peculiar fish from the Scombridae family Echeneis remora: It has on its a head a sort of oval platform on its head with adhesive properties, which it uses to attach itself underneath ships and floating bodies. I depict it here following a recent work from Joubin and Robin11 (Fig. I and VI). Its name is masculine in Latin and feminine in French.

This strange ability to let itself be transported was well known to the Ancients, only they reversed the roles. Greek and Roman authors believed the remora was graced with shocking strength and was able to carry ships, take them wherever it wanted, or on the other hand, immobilise them.

Pliny complacently echoed this belief, no doubt already very ancient in his time, and recognised the critical role played by the remora in the Battle of Actium, which took place in 30 B.C.12 I cannot resist here citing the savoury summary that our illustrious 16th century surgeon Ambroise Paré gives of the old Roman writer, to whom, it should be said, gave full credence.13

«Pliny says there was a little fish, only half a foot long, called Echeneis, otherwise Remora… which was able to restrain and stop sea vessels, no matter their size: when it attached itself on something, no matter the efforts of the sea or of the crew, despite the waves, despite the wind, despite the oars, despite the heavy anchors. And in fact, it is said that on the defeat at Actium, in the city of Albany, this fish stopped the flagship galley of Mark Anthony, who gave encouragement to the oarsmen from galley to galley. And meanwhile the army of Augustus seeing this disorder in the line, invested so suddenly Mark Anthony’s galley that they pierced it through the hull. The same happened to the galley of the Emperor Caligula. This Prince, seeing that his galley alone in all the fleet did not advance, and nevertheless had five oarsmen on every bank, understood the cause of the ship’s arrest, and sent divers to search for the cause, which they found underneath the wheel: which, being brought before Caligula, was annoyed that such a small fish had the ability to oppose the efforts of four hundred galleys and galiots. Listen to this grand and wise poet, the Lord of Bartas who gracefully says in the fifth book of the Sepmaine:

La Remore fichant son débile museau

Contre le moite bout du tempêté vaisseau,

L’arrête tout d’un coup au milieu d’une Flotte,

Qui suit le vueil du vent, et le vueil du pilote.

Les rennes de la nef on lâche tant qu’on peut:

Mais la nef pour cela charmée ne s’émeut:

Non plus que si la dent de mainte ancre fichée

Vingt piés dessous Thetis, la tenoit attachée.

Non plus qu’un Chêne encor, qui des Vents irrités

A mile et mile fois les efforts dépités,

Ferme, n'ayant pas moins, pour souffrir cette guerre,

De racines dessous, que de branches sur terre.

Di nous, Arrête-nef, dis nous comment peux-tu,

Sans secours t’opposer à la jointe vertu

Et des vents, & des mers, & des cieus, & des gasches?

Di nous en quel endroit, ô Remore, tu caches

L’ancre qui tout d’vn coup bride les mouvements

D'un vaisseau combattu de tous les Éléments?

D’où tu prends cet engin: d’où tu prends cette force,

Qui trompe tout engin; qui toute force force?14

Aelianus15 and Suetonius16 attributed to the Remora the same strength as Pliny, and with them, their contemporaries made out of this fish a charitable saviour, for, as they said, when it sees ships in unsurmountable danger during strong storms, it attaches itself to them and keeps them so firmly in a total stop that all the efforts of the hurricane and the tempest and the wave combined could not sink them.

Aristotle adds that the little fish which we call Echeneis or Remora, «serves sometimes for trials and philtres...»17 and it is curious to note that the same use has been attributed to the fossil sea urchin which is a globular echinoderm.

Lucan also speaks of the Remora

« And the sucking fish

Which holds the vessel back though eastern winds

Make bend the canvas»18

Like Ambroise Paré and Bartas, the other Renaissance authors, following the Medievals, have spoken of the exploits of this extraordinary fish, and Rabelais assures us that «with the flesh of that fish, preserved with salt, you may fish gold out of the deepest well that was ever sounded with a plummet...»19

In the 17th century, Cyrano de Bergerac, who wrote of the remora’s origins in the Polar regions, recounts the horrific duel of this «Icefish» and the «Salamander», «la fire-beast», in which the Remora triumphs.20

Popular traditions concerning the remora are not dead yet: I know from a sailor from Hyères that this fish sometimes charitably attaches itself to old dolphins, to nearly blind old sharks, and directs them to banks full of small fish feeding, and in the wake of large ships, to help them avoid crashing against reefs, etc. It is in effect possible that the strange remora attaches itself to larger animals, young or old, like it does to all floating bodies; as far as the rest goes… The same beliefs are found in the region of Capri; and in Western Insulindia they accord to the ikanghemi the same charitable character accorded by sailors in Western Europe to the remora.

The Remora in Early Christian Iconography

Primitive Christian Symbolists used the aforementioned myths attached to the remora to enter it into the bestiary of the Saviour: the ship in peril was the image of the Christian exposed on the «sea of this world»; the agitated winds and waves were those of temptation and the tribulations of this life and the remora figured Christ the Redeemer who by His grace saves, sustains, and maintains the Soul of the faithful in imperturbable security.

Or very well even, the ship shaken on the tempestuous sea was the Church, battered by savage persecutions crying out to its omnipotent founder the cry of the Apostles: Master, save us: we perish.» (Matthew 8:25). And the presence of the remora underneath the hull was the reply of Christ to his anguished faithful.

The etching on violet jasper from the Berthier collection, found in Saujon in Saintonge, which I reproduce here (Fig. II) appears to be from the 4th or perhaps the 3rd century. This carved stone is certainly of Christian inspiration: the presence of the dove with the olive branch on the stern of the ship which the remora is towing appears to demonstrate this conclusively; it also allows us to see in it an image of the Church rather than the individual believer.

An engraved carnelian dating to the Early Christian centuries depicts the ship of the Church on which the Apostles fish the fish of the faithful. Underneath the skiff, the remora assures the fishermen’s safety, and so that we don’t confuse this fish, emblem of Christ, with any other regular fish, the lapidary inscribed his name next to it: IH (IEsous) X (X restos). (Fig. III).

Most often, early Christian art shows us the ship in peril and not the remora but rather the dolphin as the «friendly fish and most consecrated emblem of Christ, pilot, guide, and saviour.» (Fig. IV).

The emblem of the remora underneath the ship traversed the first millennium, accepted by diverse variants of the Physiologus which soon inspired the mystical Bestiares of the 12th and 13th centuries.

The Bestiary of Pierre le Picard, which is from this epoch, depicts the strange fish underneath a ship up-heaved by a wave. The text explains the symbolism as follows:

«It is a fish called Essinus. Physiologus tells us that there is a fish from the Indian Ocean called essinus. This fish is less than a foot long. There is found in him such great virtue that there isn’t a ship heavy or agile enough to shake it off; it can neither move forwards nor backwards if this fish attaches itself to it. If there is a great tempest in the sea and this fish attaches itself to a ship, that ship will be completely safe, both the ship and everything inside it. In fact, many ships have been saved by virtue of this fish attaching itself to it.» (Fig. V).

«This fish is an example of our Lord, the sea is an example of the world. The ship signifies the man who lives in this world; the waves of the sea signify the temptations which the just man suffers in his century, but by the true belief and the good hope which he places in God, the man is sustained and well governed, and cannot perish, not any more than the ship which the remora attaches itself to can perish. It should be understood by this that to him who places his care in God and serves Him, God will attach himself to him and by no way can he perish...»

In the ancient or medieval depictions of the remora underneath the ship, we often see that the animal does not touch the hull. This is because the Ancients accorded this fish a loving nature, and by consequence did not need to actually touch the ship to secure it, they said it only needed to be in proximity to the ship for its powers to go into effect. This also explains why Rabelais attributed to the flesh of this fish the power to extract gold from wells and pit caves.

And this power of attraction was, for the symbolists, an image of Christ the Good and Powerful who goes looking for souls fallen into the vice in the darkest depths, precious Souls whom he spilled His precious blood for, who he «attracts to Himself to place them in his treasury».

The Remora in European Heraldry

The strange fish was there an emblem of fixity, of stopping power, of the force of inertia, of tenacity.

The Blazon, in accordance with ancient Greco-Roman traditions, opposed it to the dolphin taken as an emblem of the fast march, of velocity on the sea. We find this opposition formally expressed on numerous armouries of yesteryear, such as the heraldic and personal mark chosen by «Paul III, Sovereign Pontiff, who had as a coat of arms a Remora and a Dolphin attached to each other».

The sense of this is inspired by moderation, since one of the emblems counterbalances the other.

But when a remora underneath a ship is found on a Blazon, it is an emblem of Christ the Saviour, as on the most ancient Christian monuments.

The Pike

The Pike and the Light

When I published in the magazine Regnabit21, elements from the preceding chapters pertaining to the symbolism of fish, a French archaeologist, great friend of early Christian art, wrote to me that he was shocked by the fact that, out of all the fish represented as symbols of the Eucharist, out of all the fish that cannot but be figures of the Divine Ichthys, «many seem to, sometimes almost exactly, depict the pike», and that he was furthermore surprised that this fish, great ravager of our rivers and estuaries, which he seemed to him more fitting, did not figure Satan, ravisher of Souls, rather than Christ, the Saviour of Souls.

First things first, in effect the pike is sometimes found in primitive Christian art, in Italy and elsewhere, although not as commonly as some other fish, such as the dolphin, the remora, the perch, the turbot, and the seahorse; most of the fish are indeterminable, and even for those that can be positively identified as this or that species, the artists often did not take into account the exact number and placement of their fins. But ultimately, yes, the pike-type does exist, and one cannot say that it wasn’t due to some higher symbolic order, for, due to some of its behaviours and by its name even, this fish would have caught the eye of the creators of the personal symbolism of Christ (Fig. I, II, III).

Like a great number of fishermen and rural Frenchmen today, the Ancients said that if the pike was a devastator, it was also a great enemy for river snakes, a formidable opponent who, having attained its full size and vigour, gnashes between its teeth the body of the water viper whose powerful poison has no effect on the fish. Now, we have already said that our forefathers liked to see in pretty much every animal which hunted reptiles an image of Christ, destroyer of evil.

The Ancients knew like us that the pike frequents, most often in Summer, the clear waters near freshwater sources where it finds the small minnows which it feeds on; it could be taken as a motif of the fish that swims in clean waters, of that «Fish of the source» (literally «Ichthus of the source») of which the previously cited 3rd century epitaph of Bishop Abercius speaks of.

The name which the ancient Latins gave to this fish concorded perfectly with the mystical idea of clear purity, of limpidity: they called it, for whatever reasons they had, from very ancient times perhaps, the Lucius (Linnaeus), the luminous.

Certain people have claimed that the name came from the fact that the Ancients used the organs of this fish, like those of many other sea fishes, to prepare a sort of phosphorescent paste whose presence is revealed at night due to the faint light it emits.

Whatever it might have been, it remains possible and even probable that in the spirits of the early Christians so well nourished by symbolism, a rapprochement was made sometimes between the Lucius and Jesus, the Divine Icthus, who alone can say «I am the light of the world: he that followeth me shall not walk in darkness, but shall have the light of life.» (John 8:12).

It must nevertheless be noted that despite this symbolic link which unites the name of this fish to the idea of light, the fish which most often adorns Christian lamps was the Dolphin, as we have already seen; however it is possible to see in a few the figure of the pike (Fig. IV).

Otherwise the Ancients accorded the pike qualities of rare intelligence and perspicacity, «fine like a pike», as a saying from Tours goes. This fish must have had, in the residing, a much higher and much more ancient consecration, which will probably always remain a mystery to us, in the Paleolithic grotto of Cabarets (Lot), which was for primitive man a mysterious sanctuary, «we see, says P. Le Cour, among the animals depicted, a large pike. Now, he adds, we know what role the fish played in Christianity. Better yet, the Latin name of the pike, already from ancient times, is Lucius, the Light».

This Lucius, this lord of light, certain people claim to recognise on the staircase in the Hypogeum of Melbaude in Poitiers, dating from the 7th century, where symbolism plays an important role. Another fish follows it, incontestably an image of the faithful; between the Master and the follower, a cross. «If any man will come after me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross daily, and follow me.» (Luke 9:23).

The art of the Middle Ages, and notably the heraldic art, attached the pike to the idea of light. Thus the city of Luçon in Poitou was called in Latin Lucionensis vicus, or Lucyonum, Lucyonium; now the chapter of canons of the cathedral of Luçon, an old Benedictine abbey elevated to bishopric by Pope John XXII in the 14th century, received as armoury three silver pikes on a shield of azur. (Fig. VI), a clear allusion to the name Lucius, the supposed founder of the city and the name of the fish.

The old Fortuné Parenteau collection, today found in the Archaeological Museum of Nantes, has a méreau of a canon from Luçon in the 15th century which bears the pike (Fig. VII). In his inventory Archéologique, Parenteau writes: «Ecclesiastical méreau from the chapter of the Cathedral of Luçon. In a field a pike Lucius, and three figures. Unit I. — 15th century. Provenance, the cloisters of the abbey».

The old Luc-Fontenay family heraldry bears Azur pikes of silver posed in fasces and topped with a golden star. In this blazon all is limpidity and light. The House de Villeblanche in Brittany due to the ending of their name, have three pike heads on their blazon.

If the old French heraldists had the idea to link the pike to this idea, how could one be shocked to see that the early Christian symbolism thought to link the pike, the luminous fish, to Christ, divine fish and Light, «Light of men» (John 1:4).

In the series of emblems which the Albigensian Cathars from Languedoc preserved up until the 13th century, the symbolic fish figures under numerous varieties already mentioned, although mostly by the anonymous fish, nevertheless the pike can be recognised there, as Otto Rahn says: «the fish, symbol of Luminous Divinity».22

In the course of the preceding lines, I have figured numerous symbolic fish of the pike-type. All of them date prior to the 5th century and are of clear Christian manufacture (Fig. I, II, III, IV, V). The fish of Autun and Herpes also belong to this category, as we have seen in the chapter on Fish.

Revue numismatique, 4th series, Vol. XVII, 1913, Pl. II n. 202.

Ibid, Vol. XXII, Pl. VII and A. de Barthélemy, Nouveau Manuel de Numism. ancienne, Pl. VIII, n. 265.

A. de Barthélemy, Nouveau Manuel de Numism. ancienne, Pl. I, n. 8.

Lampridius, Alexander Severus, 56.

Tacitus, Annals, I, 79.

De Rossi, Roma sotter., Vol. II, 333 and Bulletin d’Archéologie chrétienne, 1870, p. 83, pl. Iv and 1871, p.85.

Dom Leclerq, Manuel d’Archéologie chrétienne, T. II p. 379, n. 288 and Dictionnaire d’Archéologie chrétienne, T. VI, col. 823.

Ant. Rich, Dictionnaire des Antiquités grecques et romaines, pp. 250 and 358.

Gori, Trésor des Gemmes, T. II, p. 272.

Deloche, Étude historique et archéologique sur les anneaux des premiers siècles du Moyen-âge, p. 115, n. XCIX.

Joubin, Robin, Histoire naturelle illustrée, p. 179.

Pliny, Natural History, Book XXXII, ch. 1.

Ambroise Paré, Œuvres complètes, Book XXV, p. 1067. Édition de Lyon, 1562.

The Remora tying its stupid muzzle

Against the damp end of the stormy ship,

Suddenly stops her in the middle of a Fleet,

Which is followed by the welcome of the wind, and the welcome of the pilot.

The reindeer of the nave we let go as much as we can:

But the nave for this charmed is not moved:

No more than if the tooth of many anchors stuck

Twenty feet below Thetis, kept her tied.

No more than a still Oak, which angry

Winds A mile and a mile times the frustrated efforts,

Firm, having no less, to suffer this war,

Roots underneath, so many branches on earth.

Tell us, Stop ship, tell us how can you,

Without help, oppose the joint virtue

And winds, & seas, & heavens, & strikes?

Tell us where, oh Remora, you hide

The anchor which suddenly restricts movement

From a ship fought by all the Elements?

Where do you get this machine from: where do you get this strength from,

Who deceives any machine; who all might force?

Claudius Aelianus, De Natura Animalium, IV, 17.

Suetonius, In Caio, XLIX.

Aristotle, History of Animals, L. II, X, 3.

Lucan, Pharsalia, VI.

Rabelais, Pantagruel, ch. LXII.

Cyrano de Bergerac, États et empires du Soleil et de la Lune, p. 301

Regnabit, T. XII, 1926-1927, n. 7-11.

Rahn, The Crusade against the Grail, Éditions Stock, p. 88.