A lecture given by Oswald Spengler on February 6, 1934 to the Society of Asian Art and Culture in Munich

The purpose of historical research is to depict the fate of men as far as it took place in deeds and personalities. In the past, literature was the only source used, and Ranke could say that history begins only where historical sources are available to us. Since then, the excavations have built up a new outlook and set of methods. But it must be kept in mind that the identification of strata and the ordering of finds according to formal relationships risks distracting from the real essence of history. The pottery is silent about the deeds. We would know nothing of the Germanic migrations with their figures and battles if we solely depended on archaeological finds. Among them, however, one group of artefacts always underestimated or overlooked in its real historical significance: the weapons. They are closer to history than sherds or jewelry are. They have been treated far too superficially, too much attention has been paid to their ornamentation or manufacturing technique alone. Hitherto we have lacked a psychology of weapons. Every weapon also speaks of its style of fighting and thus of the bearer’s outlook on life. There is an ethos in the invention, spread or rejection of certain weapons. For example, the bow, which was the first long-range weapon, was instinctively rejected as unchivalrous by a set of European tribes, including, among others, the Romans, the Greeks of the motherland, and most Germanic tribes. Therefore, in the depictions of the Ionic Odysseus legend on Corinthian and Attic vases, the bow necessary to mark the scene is set aside and Odysseus is given a sword, the weapon of man-to-man combat.

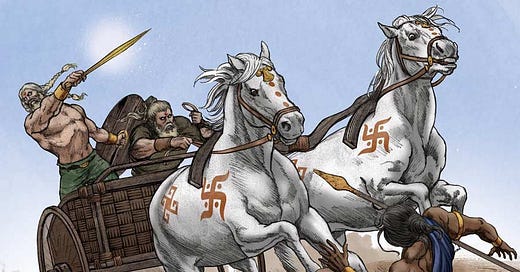

No weapon has become so world-changing as the war chariot, and that includes firearms. It is the key to understanding the history of the 2nd millennium BC, which changed the world the most in all of history. It is the first complex weapon: the actual chariot, the steering of the tamed animal, the arduous training of professional warriors, whose purpose in life was this fight from above. All these elements must coalesce. Above all, it is here that speed first enters world history as a tactical weapon. The emergence of cavalry—in the same place— is only a reaction to the consequences of chariot combat. It is a unique invention, which arose from the innermost vital impulse of an until then completely new kind of man.

The question is how, where, and when. Naive concepts like «invention of the chariot» and «acquaintance with the horse» do not remotely touch on the problem. It is a matter of three fundamentals: fast steering, the training of the horse for this purpose, and the handling of the weapon under these conditions. Only all three joined together make up the tactical thought.

Strictly speaking, we are not dealing with wagons, but carts. The four-wheeled cart is a truck, slow and load-bearing. It evolved from agricultural or cultic necessities1. This two-wheeled cart, however, is light and fast. The draught animal goes at a gallop or a trot, not a walk. Here, the problem of the roadway is always forgotten. The truck, which has to be touching the ground with all four wheels, demands a leveled road embankment or paved yard. It’s a question of short distances, a via sacra or the path from the field to the village. The war chariot, however, presupposes an open, dry, level terrain where its possibilities can unfold at any time. The battle terrain therefore excludes as a place of origin mountains, forests, and swamps, and thus almost all of Europe and the Near East.

Then there is the choice of animal. The truck is pulled by cattle or donkeys—sluggish, calm, strong, good-natured animals that walk slowly, in an almost ritualistic manner. The horse, on the other hand, is in and of itself far too fast and spirited. It was a bold discovery to see such tactical possibilities in him. The talk of «acquaintance with the horses» is nonsensical. Wild horses were everywhere in Asia and Europe. They were hunted and eaten; nothing else is proven by the old West European finds. Here, however, the horse is captured and tamed, and even more: trained and bred for this purpose as a runner. It is the oldest systematically refined animal breed that we know. The breeding of the riding horse about a millennium later is only the last consequence. In addition, there is the intention to fully assert the superiority of this weapon against all others. Tempo as a weapon thus enters the history of war, and also the idea that the professional warrior skilled in combat is an estate2, and indeed the most distinguished one among the people. With this weapon comes a new kind of man. The joy of daring and adventure, of personal bravery and chivalrous ethos, assert themselves. Master races emerge who view war as their purpose in life and look down with pride and contempt on peasants and cattle-herders. Here, in the 2nd millennium BC, a new kind of manhood which was not there before expresses itself. A new type of soul is born. From then on, there is a conscious heroism.

Fifty years ago, the chariot was only known from Homer. Today, we know that the tribe that left behind the shaft graves in Mycenae3 fought there with this weapon in the 16th century BC. But in the same period began the movement of the Hyksos in the Near East. That there was a name full of terror that the Egyptians coined and never forgot: Rulers of foreign lands. Their language and race are unknown. They came from the North, not from Syria, but from Armenia and from regions even more distant, behind them not a unified people, but rather conquering swarms, either allied with each other, or fighting each other, but who all felt that ruling and plundering was the purpose of life and made the subjugated work for them. Farther east, likewise, around 1700 BC, the Kassites descended upon Babylonia, and still farther east the Aryans fell upon the old Indus culture, which we have known for some years from the excavations at Mohenjo Daro and Harappa. In the old, genuine parts of the Indian epic, the ethos of these conquerors strikes us exactly as in the Iliad. But, what to my knowledge hasn’t been recognised at all: It was much the same in China. We know today that the picture of ancient Chinese history up to the Shang dynasty was an invention of Confucian scholars. The bone finds in Henan with their completely undeveloped writing have taught us that at that time there could be no question of political records. Real history does not exist here earlier than in India and Greece, i.e. since the second half of the 2nd millennium BC. But from the very beginning, firm tradition has preserved the knowledge that, here as there, a conquest of the Master people took pace with war chariots. The Zhou were among them. Since then, as in the West, the chariot has been the pivotal and aristocratic weapon that decided the outcome of battles even during the early Han period. In this larger context, the history of China since 1200 BC can be better understood: It is based on the same mental premises as in India and the Classical world.

The chariot and the group of the chariot peoples thus have their origin in the great steppe which stretches from southern Russia to Mongolia and which at that time was not as desertified as today. From here later the equestrian tribes descended upon Europe and Asia. It is the old conqueror’s road, on which the Scythians, Cimmerians, Huns, Bulgarians, Turks, and the Mongols of Genghis Khan advanced to the West, East, and South. We know scarcely anything of the language and race of the chariot people. They may have been diverse enough, especially since such conquests rouse and sweep away other peoples. The decisive point, however, is that it was not a matter of the displacement of peoples by the seizure of peasant land and cattle pasture, but of the superimposition of a heroic barbarism on more highly cultivated peoples. With the chariot begins over the old world a wild confusion of splendor and ruin, a whirl of races and languages of every kind. Ephemeral states arise, great leaders appear and disappear, adventurers and warlords intervene devastatingly in the course of history. The result for world history is tremendous. It has acquired a new style and meaning. Hyksos and Kassites have overthrown the old southern cultures; scarcely that some Pharaohs and Assyrian rulers, perhaps themselves related by blood to these conquerors, successfully took up their style for the rest of their lives. Three new master cultures of a chivalrous character arise over a subjugated, highly civilized population: the Greco-Roman over the Minoan-Mycenaean, the Aryan over the ancient Indus culture, the "Chinese" over a more southerly one for which we have no name. Instead of the Egyptian official and the Babylonian priestly nobility, an aristocracy of arms is formed here. War is the raison d'être of the ruling class. These more northern cultures are more manly and energetic than those of the Euphrates and Nile. They have a different sense of distance and destiny. But the master class of early times begins to slacken in the southern warmth, earliest and most thoroughly in the southernmost of them, the Indian. There begins a struggle of the old local lower class against the culture-bearing aristocracy, whose will, thoughts and feelings are ultimately consumed: that is the tragedy of these three historical processes.

Presumably referring to the transportation required for the building of Megaliths sites - Tr

Estate or class, it’s difficult to translate the German ‘Stand’ - Tr